Meta: Fad or Future?

As hinted at in my last post, there has been an oddity in the closing months of 2021 that warrants a closer look: namely the name change (pun intended) of everybody’s favorite social media giant.

In a rather unforeseen move, the humanoid going by the name Mark Zuckerberg took to the stage and ordained that Facebook henceforth be known as Meta. The humanoid then pushed its acting skills to the brink in an hour-long attempt to conjure up a future where the real and virtual world would seamlessly blend into one another.

Knowing full well the limits of its charm, the biped relied on the term Metaverse to carry its vision across. This supposed Internet successor is supposedly just around the corner and will—as the name supposes—take on the form of an entire universe. Though there’s frequent emphasis on the word together, it seems apparent that the Zuckerberg organism envisions itself at the center of this new world—if not as its outright demiurge.

In order to turn this vision into (virtual) reality, Facebook / Meta is ostensibly banking on its Oculus technology as well as the empty stomachs of content creators and the corporate elite’s unending hunt for tighter wage cages.

This news piece dropped at a time when Facebook found itself embroiled in yet another data privacy scandal, so naturally the announcement was met with widespread mockery across the Internet. Perhaps contrary to common sense, the furious meming didn’t hurt the company’s bottom line but might have acted as free publicity instead.

This begs the question: what was the true reason for the name change? Does Meta actually intend to remake the digital landscape or is it all just hot air?

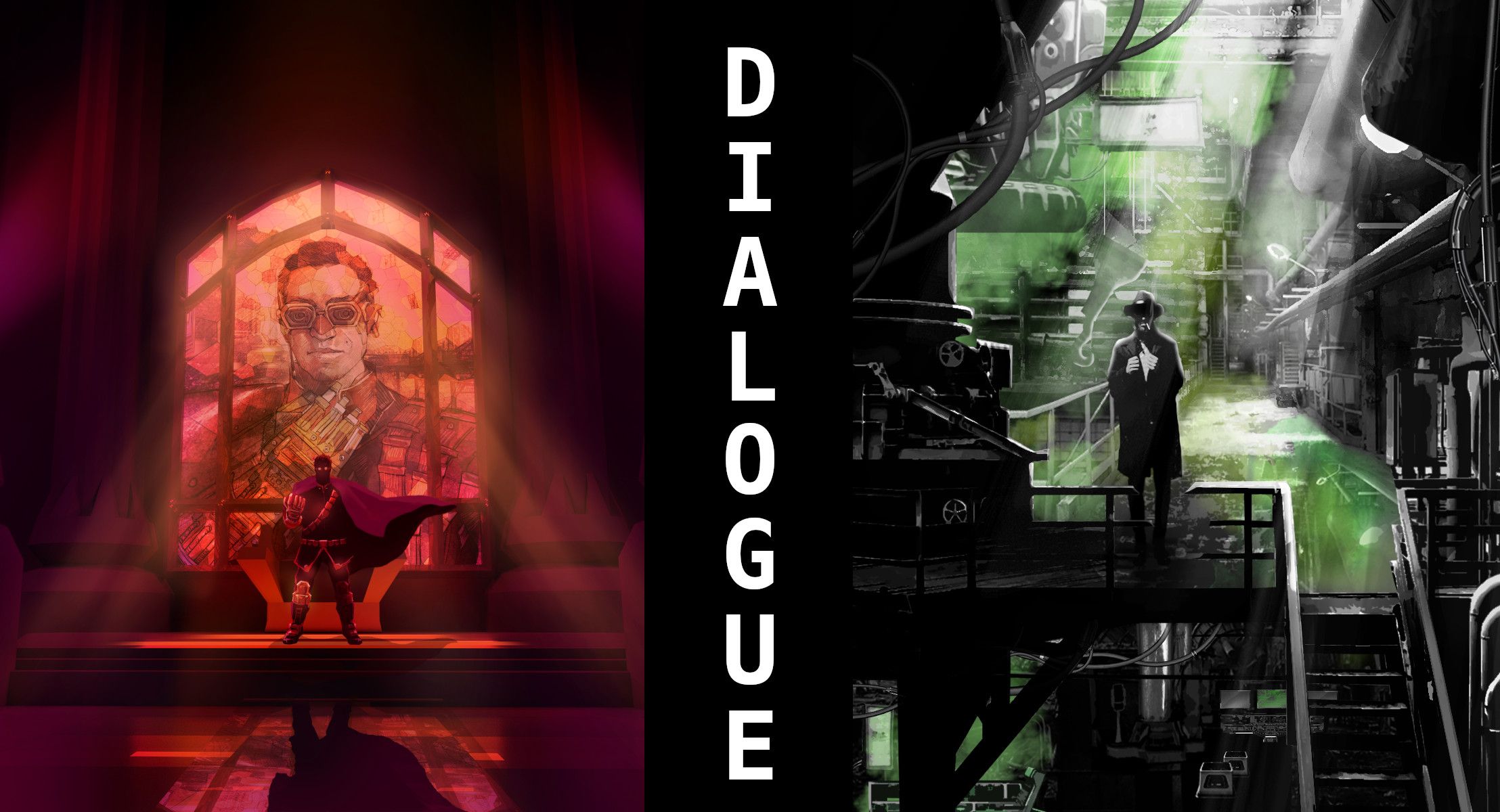

As much as I hate to say it, I guess we won’t be able to untangle this matter without a propagandist’s eye. Hence it is my displeasure to welcome the slippery Dr. Kramer once again. Together, we shall try to discern the true intentions of the Zuckerberg organism and evaluate probable futures.

Eliphas: Happy to be of service, though I didn’t expect to be reinvited so soon. It is surprising that the ever-scheming Klotz Van Ziegelstein would make room in his schedule for the twitches of a dying empire.

Klotz: Dying? What makes you say that?

Eliphas: The signs have been there for years. Facebook is running out of steam and its demise a certainty. Zuckerberg needs another eureka moment. A new bottle to capture lightning—i.e. users—in.

Klotz: Right then, Dr. Kramer. Illuminate us.

Eliphas: You know what I’m going to say.

Klotz: Of course, you’ll want to bore us with definitions first. Any particular starting point?

Eliphas: You mentioned the term Metaverse. Let’s start with that.

Klotz: Very well.

Origin of the Metaverse

Klotz: Interestingly enough, the Zuckerberg organism didn’t give birth to the Metaverse concept, it merely adopted it—and it wasn’t even the first to do so. The crypto community has been hyping Metaverse-ish ideas for a while now, particularly during the DeFi craze—and the more recent NFT bubble.

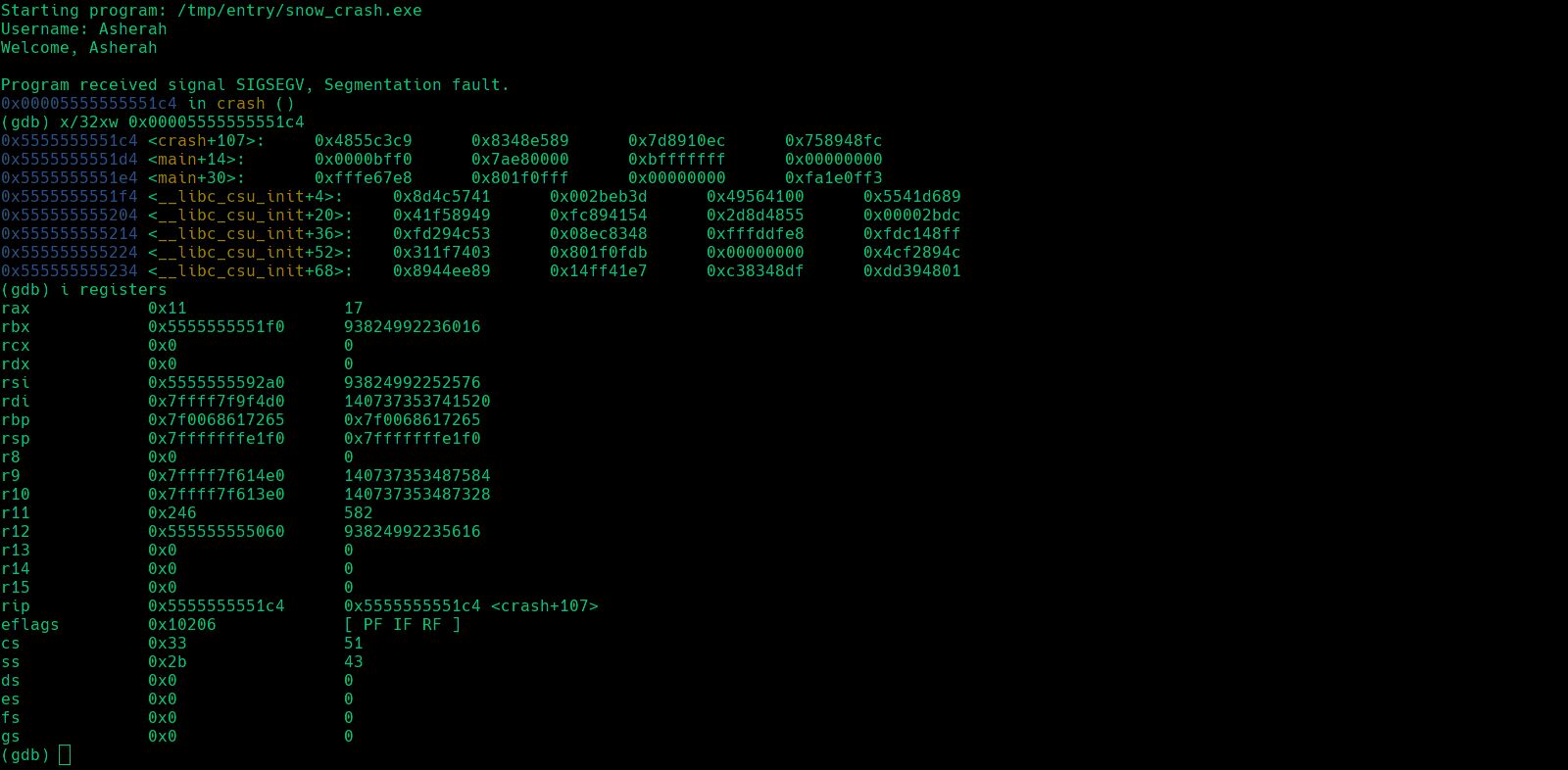

The concept predates both Facebook and cryptocurrencies, however, as it was initially described in the novel Snow Crash. This is not just any old book but a foundational pillar of the cyberpunk genre—which makes it all the more ironic that a megacorporation is now tying it to its helm.

Hiro is approaching the Street. It is the Broadway, the Champs Élysées of the Metaverse. It is the brilliantly lit boulevard that can be seen, miniaturized and backward, reflected in the lenses of his goggles. It does not really exist. But right now, millions of people are walking up and down it. The dimensions of the Street are fixed by a protocol, hammered out by the computer-graphics ninja overlords of the Association for Computing Machinery’s Global Multimedia Protocol Group. The Street seems to be a grand boulevard going all the way around the equator of a black sphere with a radius of a bit more than ten thousand kilometers. That makes it 65,536 kilometers around, which is considerably bigger than Earth.

— Snow Crash, Chapter 3

Klotz: Neal Stephenson’s breakthrough novel has a lot in common with Neuromancer, another cornerstone of the genre—briefly touched upon during our assessment of CD Projekt’s failure. Both books paint a bleak future where faceless conglomerates rule and the average Joe has an equal chance of being assailed by ads and psychopathic assassins. Furthermore, in both books the Internet has been supplanted by a virtual world—only Neuromancer uses the term Cyberspace instead of Metaverse.

Eliphas: The novels are only similar in the most superficial way. It needs to be highlighted that in contrast to William Gibson—who has never worked as a programmer himself—Neal Stephenson has a scientific background and must have compiled his own binaries at some point. This can be seen in the paragraph that follows the snippet you just quoted:

The number 65,536 is an awkward figure to everyone except a hacker, who recognizes it more readily than his own mother’s date of birth: It happens to be a power of 2—216 power to be exact—and even the exponent 16 is equal to 24, and 4 is equal to 22. Along with 256; 32,768; and 2,147,483,648; 65,536 is one of the foundation stones of the hacker universe, in which 2 is the only really important number because that’s how many digits a computer can recognize. One of those digits is 0, and the other is 1. Any number that can be created by fetishistically multiplying 2s by each other, and subtracting the occasional 1, will be instantly recognizable to a hacker.

— Snow Crash, Chapter 3

Eliphas: Indeed, I did instantly recognize the number 65536 and so will anyone who’s ever had to configure a firewall. This imbues Stephenson’s Metaverse with greater authenticity. It is probably also the reason why Snow Crash can be found on many a shelf in Silicon Valley—together with the Cryptonomicon, the second book that Stephenson is famous for—whereas Neuromancer’s readership consists primarily of non-tech people.

Klotz: You’ve made your preference clear, doctor. Let us not pretend, however, that Snow Crash is plausibility incarnate. Or are you a proponent of the neurolinguistic programming ideas outlined in the latter half of the novel?

Eliphas: I’m not. The whole bio hacking twist is where the book clearly departs into fiction. There’s no need for an ancient master language in order for humans to be programmable. We’ve already discovered better tools—PR and marketing.

Nonetheless, I maintain that Stephenson had greater foresight than Gibson, particularly in regards to the maturing of the Internet. In the future of Neuromancer, hackers—exemplifying the most knowledgeable and creative minds of the digitalized world—still exist somewhat outside of the corporate complex. The book calls them console cowboys and that’s exactly what they are: rebels whose resourcefulness allows them to roam free in Cyberspace. The most skilled drifters—e.g. McCoy Pauley or Bobby Quine—can go toe-to-toe with nearly any kind of organization, no matter its size.

The power and untamable nature of Gibson’s hackers is distilled in the following snippet from Count Zero, the successor novel to Neuromancer:

The Wig, in his first heat of youth and glory, had stormed off on an extended pass through the rather sparsely occupied sectors of the matrix representing those geographical areas which had once been known as the Third World. Silicon doesn’t wear out; microchips were effectively immortal. The Wig took notice of the fact. Like every other child of his age, however, he knew that silicon became obsolete, which was worse than wearing out; this fact was a grim and accepted constant for the Wig, like death or taxes, and in fact he was usually more worried about his gear falling behind the state of the art than he was about death (he was twenty-two) or taxes (he didn’t file, although he paid a Singapore money laundry a yearly percentage that was roughly equivalent to the income tax he would have been required to pay if he’d declared his gross).

The Wig reasoned that all that obsolete silicon had to be going somewhere. Where it was going, he learned, was into any number of very poor places struggling along with nascent industrial bases. Nations so benighted that the concept of nation was still taken seriously. The Wig punched himself through a couple of African backwaters and felt like a shark cruising a swimming pool thick with caviar. Not that any one of those tasty tiny eggs amounted to much, but you could just open wide and scoop, and it was easy and filling and it added up. The Wig worked the Africans for a week, incidentally bringing about the collapse of at least three governments and causing untold human suffering. At the end of his week, fat with the cream of several million laughably tiny bank accounts, he retired. As he was going out, the locusts were coming in; other people had gotten the African idea.

— The Finn recounting Wigan Ludgate’s deeds to Bobby Newmark

Klotz: I was actually about to quote this exact passage myself, Dr. Kramer. For you see, your efforts to belittle Gibson achieve the opposite. The dot-com era had its own McCoy Pauley and Bobby Quine in the likes of Jonathan James (going by the handle c0mrade) and Michael Calce (aka MafiaBoy). These guys were every bit as untamable and dangerous as Gibson’s console cowboys.

In fact, let me remind you of how Angelina Jolie made her Hollywood debut:

Klotz: This long-forgotten flick cared little for technical accuracy. Yet that didn’t stop it from molding hacker culture in its image. This influence can be seen in early hacker groups like MOD (compare handles like Acid Phreak and The Plague to the names from the movie). What started out as a goofy on-screen rebellion was reenacted in reality. And the rampage has continued ever since, with groups such as Anonymous and LulzSec vandalizing whatever digital property they came across. It is a classic case of media reshaping its audience, something I’m sure a propagandist will appreciate.

Eliphas: You’ve got it backwards. The Masters of Deception were active before the movie’s shooting. Thus Hackers was a snapshot of existing hacker culture and may only have acted as an amplifier—I see that the great Van Ziegelstein is allowing himself to get sloppy in my absence.

Your shallow research aside, notice how far back in time you had to go to make your point. The current year is 2022—in case you’ve forgotten—and the days of phreaking are long gone. The hackers of old are either dead or retired, having traded the garbled patterns of hex dumps for corporate desks or book deals.

Gibson’s vision did capture reality, that is correct. The fault lies in the fact that it captured the reality of the 90s, not the future.

Stephenson, on the other hand, foresaw what would become of the lone code cowboy:

“It’s fucking hard,” Hiro says. “There’s no place for a freelance hacker anymore. You have to have a big corporation behind you.”

— Snow Crash, chapter 9

Eliphas: Early on in the story, we learn that the protagonist—aptly named Hiro Protagonist—is struggling to monetize his skills, despite being one of the Metaverse’s founding programmers. Chapter 5 provides us with a why for this paradoxical situation:

When Hiro learned how to do this, way back fifteen years ago, a hacker could sit down and write an entire piece of software by himself. Now, that’s no longer possible. Software comes out of factories, and hackers are, to a greater or lesser extent, assembly-line workers. Worse yet, they may become managers who never get to write any code themselves.

— Snow Crash, chapter 5

Eliphas: Writing code is a complex task, and the complexity only increases the more parameters come into play—or, to use proper lingo: “the more the problem space grows”. This aspect of software development is strangely absent from Gibson’s Cyberspace but ingrained in the very history of the Metaverse.

In the book, the Metaverse starts as an empty street, populated exclusively by hackers and their sketchy 3D models. As these pioneers refine their code and make the street more hospitable to laymen, more people pour in. This influx naturally produces a demand for more elaborate functionality, which in turn places a heavier burden on the pioneers. Soon, the complexity grows to a point where a single project—e.g. the creation of a multistory adult entertainment venue with fluorescent walls and other fancy effects—can no longer be tackled by a single hacker. Instead, the street’s pioneers have to get organized and form dedicated teams.

Structure, manpower, resources—these are all things that corporations are designed to provide. Hence it is no surprise that Stephenson’s hackers don’t oppose the “megacorp takeover” of the street but participate in it. Hiro’s friend Da5id even founds and IPO’s his own company, the Black Sun.

So while Gibson presented us with the romantic notion of a digital Wild West, Stephenson ventured further and into the post Wild West. The Metaverse’s hackers have traded their cowboy hats for the white collars of the office space. This is emphasized at the very start of the book:

But he wouldn’t drive for CosaNostra Pizza any other way. You know why? Because there’s something about having your life on the line. It’s like being a kamikaze pilot. Your mind is clear. Other people—store clerks, burger flippers, software engineers, the whole vocabulary of meaningless jobs that make up Life in America—other people just rely on plain old competition. Better flip your burgers or debug your subroutines faster and better than your high school classmate two blocks down the strip is flipping or debugging, because we’re in competition with those guys, and people notice these things.

— Snow Crash, Chapter 1

Eliphas: Of course, Hiro’s still clinging to his weathered cowboy hat, which is why he finds himself in his unfortunate predicament.

Klotz: You know, I’m actually starting to see how the novel might fuel the ambitions of a Zuckerbergian intellect. Perhaps the statement of being a fan of the book wasn’t just hollow PR speak.

Eliphas: You’d have met Peter Thiel and Jeff Bezos in Zuckerberg’s reading club as well—the latter even employed Stephenson as an advisor for his Blue Origin project. The novel outlined the trajectory of the Internet and those involved in its creation. Like Hiro and his companions, most of the Valley’s leaders underwent the transformation from code geek to entrepreneur.

Notice also how Stephenson didn’t invent a new term for the tech-savvy crowd of the Metaverse but stuck to the existing word hacker. The book’s characters occasionally throw around more contemporary labels for code crafting as well. That doesn’t change Hiro’s view on every programmer being a hacker first and foremost.

Our world mirrored this evolution of terminology. Back in the day, when a smartphone’s processing power would take up an entire warehouse and coding was an arcane art, all masters of the craft were hackers. It was only once the first network intrusions made waves in the media that the term was narrowed to refer to malware authors alone. As the education complex ramped up its production of computer scientists, the craft became less arcane and more of a commodity, ultimately culminating in the birth of sanitized job labels such as front / back end developer, software engineer, system administrator, DevOps engineer etc.

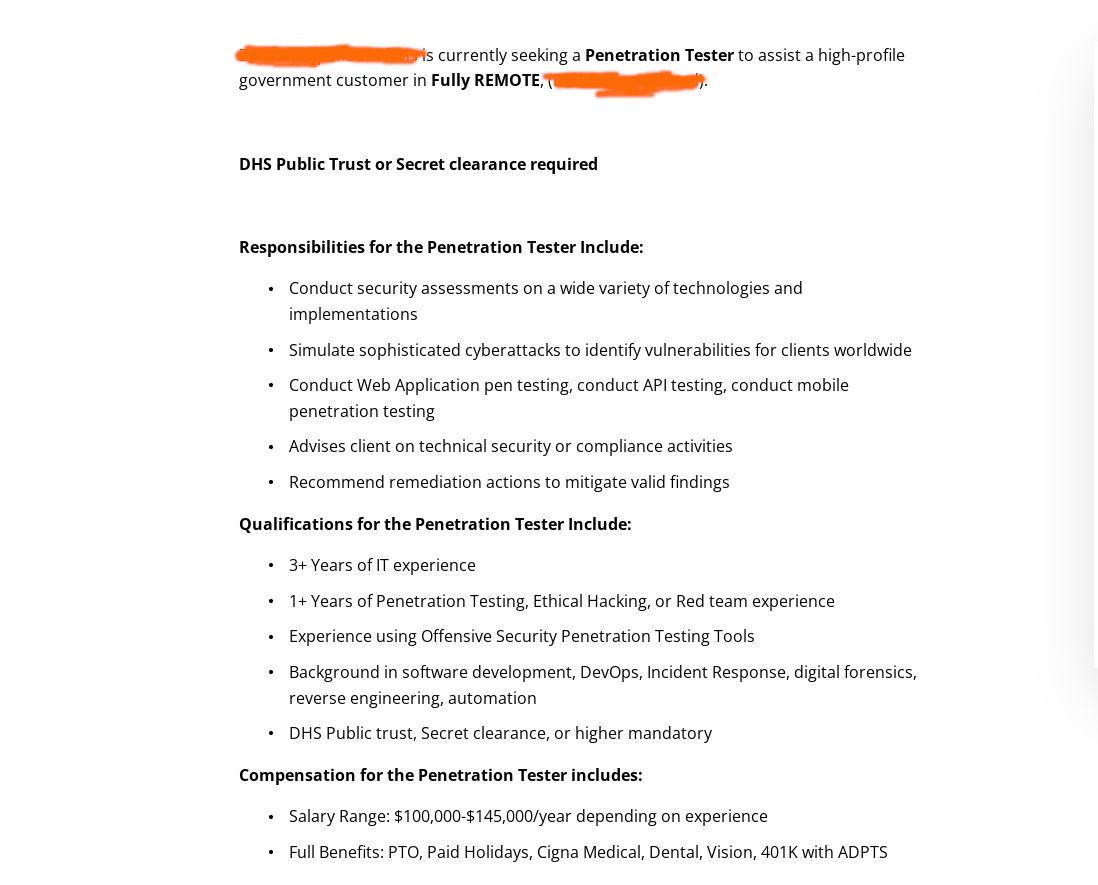

Even hacking in the media-muddled sense of the word has turned into a nine to five, complete with its own HR tag—penetration tester. Consider this randomly selected job ad:

Eliphas: You get the premium care package, dental and eye checkups included. There are thousands of similar openings floating around the web.

I’d also like to direct your attention to the government customer mentioned in the ad, so as to spare us both the examination of collectives such as the Lazarus Group or Tailored Access Operations. Most of today’s high-profile hacking incidents are executed by state-controlled actors. Case in point: the SolarWinds hack as—presumably—orchestrated by the Russian Nobelium group.

I think we can both agree that working for the government is the opposite of cowboy life. You might ask where all of these institutions shop for personnel, since there is no such thing as an Exploitation Science Major. The answer is simple: the contemporary hackers are churned out en masse by dedicated online boot camps, then put to work in labor pools mimicking the successful Upwork model.

Klotz: Ah, what a tragic tale. To see such an esteemed craft reduced to a mere Fiverr gig.

Eliphas: It’s not tragic. It’s the logical consequence of the Internet’s success. Stephenson’s vision was prophetic.

Klotz: There are still holes in his prediction, Dr. Kramer. For one, every Metaverse traveler gets the same version of the street. There are no discrepancies, no personalized illusions. This is different from the current Internet, where no two Facebook feeds, no two Twitter or Google SERPs are the same. Each user gets served with their own little universe, fine-tuned to their expectations and biases.

And because there aren’t multiple versions of the truth, Stephenson’s Metaverse must do without the jovial cries of ideological crusades.

Eliphas: That is because Stephenson is not a propagandist. It would have taken both a hacker and a social scientist to foresee the impact of Facebook’s content algorithms.

I’m actually surprised that I have to act in Stephenson’s defense here. I expected us to be on the same page, given what you saw in your own little crystal ball. Allow me to quote from your writings:

There they brooded, the self-styled demons of the 30th century, scattered across the rows of the ruined theater. Most had either fashioned themselves into nightmare creatures or bland suits with slicked back hair. Testament to the dualistic strain of entrepreneurial occultism that ran through nearly all shadow guilds.

— Pillagers, Chapter 5 (hasty translation)

Eliphas: If your own prophecy regarding the neobarbarians is to be believed, then the virtual reality of the future will be fought over by disembodied minds that are nevertheless organized in strict hierarchies. This bears greater semblance to Stephenson’s vision than to Gibson’s.

Klotz: The semblance is only there in the most superficial way—to use your own words. First, the Internet successor that we get to experience in Pillagers is called Omninet—a meaningless terminological distinction, I know. Second, the inhabitants of that future are directly hooked up to the digital world via brain implants. This is closer to what Gibson described than the goggles of Snow Crash.

And third, the shadow guilds are made up of spirits whose ultimate goal is to shed all remnants of humanity. They are not hackers. They are ghosts stalking the dark corners of computer networks and human minds alike, eager to corrupt any kind of thought process.

Eliphas: What this poetic summary omits is that the guilds don’t shy away from materialistic pursuits, lining their pockets with the profits of megacorporations and orchestrating the rise and fall of public figures.

Klotz: Why, it sounds like you did read the manuscript after all.

Eliphas: I considered it my duty to the tribe.

Klotz: A tribe you’re no longer part of, don’t forget that.

Eliphas: You need not concern yourself, my memory is infallible. I must ask again, though, why dismiss Stephenson’s vision?

Klotz: Do not twist my words, Dr. Kramer. I’m not dismissive of Stephenson. Rather, I have certain reservations about the Metaverse idea as it is presented by Facebook’s humanoid figurehead.

Let me elaborate …

Of Moonshots and Botched Rocket Launches

Klotz: As you said, Dr. Kramer, the year’s 2022 and the days of old-school hacking are over. No longer confined to the parking lots of Silicon Valley, innovation now happens at a global scale, with disruptive technologies surfacing from all corners of the earth.

The most prominent example of this trend is Bitcoin, which was proposed on a mailing list by its—still unknown—author.

Klotz: Though the tech industry has become synonymous with disruption, its own business model has remained largely unchanged, with startup hubs in Europe and Shenzhen copying Silicon Valley’s formula almost verbatim.

The centerpiece of said formula is the moonshot: technology so transformative that it has the potential to alter human existence in some fundamental way. Something like the personal computer. Or the atomic bomb. Or a virtual universe.

The Valley’s old guard takes the development of moonshots very seriously. Google has an entire branch—the infamous X Division—whose sole mission is the assembly of the next dot-com rocket.

As for the reason why the industry has settled on exactly this formula …

Eliphas: Fear and greed made them settle on it. In the case of Big Tech, they are aware that technological disruption does not discriminate. Even the most entrenched Internet giant can be dethroned by a fledgling company. Just ask Yahoo.

In the case of the startup scene, which makes up the other half of the industry, the dynamics of venture capital and the challenges of the early growth stage have all but eliminated alternatives to the moonshot formula.

Klotz: That’s what I was about to say. Since you touched upon the dynamics of venture capital—this looks very much like tech’s initial chicken and egg dilemma to me. What really came first? Investors’ desire to offset the monumental risk of their positions with monumental returns? Or was it rather the monumental growth of the Valley’s pioneer companies that made investors expect such results?

Maybe you have deeper insight into this matter, but to me there’s no clear answer here.

Eliphas: Little is to be gained from finding a definitive answer. Ultimately, the dynamics are what they are. Big or small, all tech companies aim for the moon. And no doubt Zuckerberg believes the Metaverse to be the crater where he can plant his next flag.

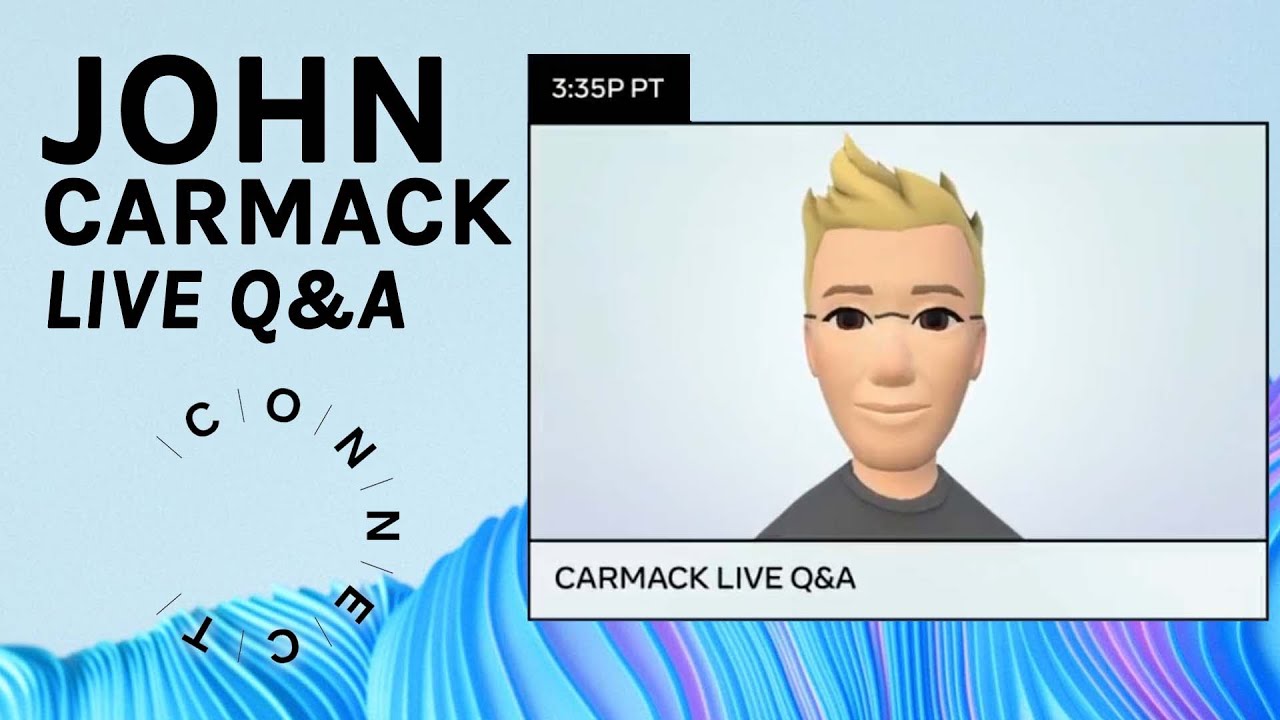

Klotz: The organism will have to reach the crater first. Not all moonshots are successful, as we know, and the likelihood of this turning into Facebook’s Apollo 13 is not small at all. Take a look at what the head of the Oculus project had to say about Meta’s progress:

Klotz: This video stands in stark contrast to the official Meta reveal, and it makes me think that the Zuckerberg biped is in for a (very unpleasant) reality check.

Some younger members of our tribe might be unfamiliar with John Carmack. I should clarify that this guy is not one of the engineering department’s rank and file but an ancient legend of the Valley.

John Carmack developed game engines before the term game engine existed, and he was the workhorse that put the world’s most iconic first-person shooter over the finish line: Doom, a video game so influential that old Bill himself hitched a ride on the bandwagon to peddle his operating system to the masses.

Eliphas: A note on terminology: you used the label first-person shooter. The term first-person derives from the fact that such games—seemingly—drop the player straight into the action. Albeit logically sound, the label first-person shooter is more recent than the category of video games it seeks to describe. Originally, all shooter games with a Doom-like perspective were called Doom clones.

Klotz: For once an interesting bit of terminology. One could argue that the term Doom clone is still applicable to today’s first-person shooters, as the core mechanics don’t seem to have changed much. Carmack’s brainchild continues to be the Alpha and the Omega of this particular entertainment niche. It is possible that he’ll leave behind an equally insurmountable legacy in the field of VR. But will it be enough to fuel a moonshot?

In his keynote, Carmack stresses that the focus needs to be on product rather than tech for tech’s sake. He also nonchalantly discloses that a lot of Quest 2 rigs are gathering dust in closets. This is an indicator that VR is still years away from producing another 2007—Steve’s original iPhone reveal.

Yet another 2007 is exactly what’s needed here. For history to repeat itself, however, several stars will have to align in Facebook’s favor:

- Technological challenges must be overcome.

- The final product must be affordable to the masses.

- The average Joe, Jane, and the gender spectrum between them must actually desire the product.

The intellect animating the Zuckerberg humanoid seems to be determined to put the cart before the horse, focusing on technical hurdles alone while taking the Metaverse’s appeal for granted. The Internet is littered with the derelict websites of companies that committed the same mistake.

I have to agree with Carmack’s assessment towards the end of the video: while people have evolved to carry smartphones and tablets around with great enthusiasm, this enthusiasm is unlikely to extend to the bulky controllers and headgear of contemporary VR devices.

Ultimately, the most ideal kind of equipment for mass appeal would be no equipment at all—the fabled experience machine. Once the virtual has become as convincing as the real and the transition between the two a matter of plugging in a cable into its socket, that is when widespread adoption will set in. At least that’s my prediction.

This is also the reason why I don’t judge Neuromancer as inferior to Snow Crash. The console cowboys enter Cyberspace by attaching trodes to their foreheads, bypassing the issue-riddled landscape of audiovisual stimulation in favor of a direct neural uplink. This concept always struck me as more efficient and consumer-friendly than the goggle approach, exactly what I’d expect from a product intended for the mass market.

Eliphas: The trodes are a superior solution. In theory. The problem is that we’re not even remotely close to unlocking such technology. The brain-computer interface is a fantasy.

Klotz: Is it?

Eliphas: Your own case is unique, and I highly doubt any sane individual will want to follow in your footsteps. Besides, it appears clear to me that the tech responsible for your indeterminate state is a scientific dead-end—at least as far as BCIs are concerned.

And given your past run-ins with Mr. Rocket Man, I don’t assume you are betting on the Neuralink media company to produce anything other than vaporware.

Stephenson’s goggle-based technology is the more plausible contender.

Klotz: A contender that takes legacy television as its template. The goggles from Snow Crash are actually more primitive than what we have today, with the digital image having to be projected by an external computing unit—utilizing a swiping beam similar to that of the old cathode-ray tube.

This concept may have meshed well with the technology level of the 90s, but to Generation Selfie it must come off as horribly quaint. It certainly doesn’t strike me as something the broad public would use.

You’ve bashed the realism of Neuromancer, doctor, but Snow Crash requires its own mental gymnastics: we’re supposed to believe that a populace of ad-addled hyper consumers with the attention span of one CPU cycle somehow has the nerve to fiddle around with cumbersome technology for what is—at best—a subpar hallucination. All of this in a world where cheaper alternatives like Cannabis exist.

Meanwhile, in our reality, the more advanced Oculus rigs are wasting away in storage rooms.

Eliphas: You see, I agree with you and Carmack that VR is in dire need of improvement. However, I don’t think that mass appeal is stifled by the physical properties of the VR devices themselves. What truly prevents another 2007 from happening is the world inside the goggles.

Connect 2021 didn’t just feature auditory propaganda. John Carmack actually demo’d the current state of Oculus in another presentation. Let’s have a look:

Eliphas: I think an objective statement can be made that this iteration of the Metaverse is still a far cry from Stephenson’s vision.

- The jittery motions of the avatars indicate that there are still a lot of scaling issues with the netcode.

- Pay attention to the clipping of the microphone. The routines for collision detection are in their infancy.

- No one wants to be a floating torso, so legs will have to be added at some point. This is an entire problem space of its own, and technology-breaking bugs may be lurking in its uncharted depths.

These details aside, there’s a more pressing issue—an issue that is as much a question of public opinion as it is of technology.

Since the turn of the millennium, people have been wading through digital content. Content that has grown ever more rich and sophisticated. Content that has raised the bar for future content.

You referred to Doom as the Alpha and Omega. The franchise has come a long way since Bill brandished a toy gun in front of a green screen. This is the latest installment:

Eliphas: From a technical standpoint, it is of course unfair to compare VR graphics to those of a video game. The public has no notion of fairness, though, and will make the comparison. Consciously or subconsciously.

And the prototype environments of the current VR landscape don’t hold up well against the spectacle that is triple-A gaming. A standard consumer who has grown fat on a diet of Pixar movies and Call of Duty sequels is unlikely to feel anything but disappointment at what is flickering inside the Oculus lenses.

It is as John Carmack said: the 21st century has optimized itself for the screen, to a point where reprogramming of the mass consciousness is no longer an option. Instead, VR has to cater to people’s marriage with screens, replicating the intricacies of the relationship as close as possible.

Only when setting up a date in the Metaverse is as low-effort as swiping right on a smartphone screen will VR stand a chance of overcoming society’s inertia.

Klotz: Your route towards mass adoption promises to be even more harrowing to the Zuckerberg organism and its associates. Which brings us back to the initial question of this analysis. Do you believe Facebook actually intends to follow through on its announcement? Or is the entire Meta story just an elaborate PR stunt?

Eliphas: It is more than a stunt. Zuckerberg will do as he said and throw his full weight behind the Metaverse idea.

Klotz: But why? As removed from reality as those in the top one percent must be, I can’t imagine this specific humanoid coming out of standby one day and spontaneously deciding to sink its entire fortune into what is essentially not a moonshot but a child’s sketch of a moonshot.

Eliphas: Zuckerberg has no choice. I’ll explain.

Facebook’s Slow, Agonizing Death

Eliphas: Zuckerberg’s empire may project the image of an unstoppable behemoth. But behind this facade is a terminally ill patient.

To regurgitate an old saying: “if it’s free, then you’re the product.” Facebook has never been about technological innovation. It is, as Zuckerberg himself said, about “connecting people”. The term people referring to propagandists and their prospects.

Klotz: You’re glossing over the company’s (proprietary) face recognition tech. This algorithm didn’t materialize out of thin air, and neither did the routines driving today’s content feed. As much as I detest having to compliment this specimen, Zuckerberg was a pioneer in its own right, though its achievements are less tangible than Edison’s light bulb.

Eliphas: My statement was not about the presence of innovation but it being part of the business model—which it hasn’t been, up to this point. Facebook has always been aimed at men like me. Advertisers, PR professionals, hucksters, use whatever word suits you best—I, of course, will stick to the traditional label propagandist.

So, what is it that—for a long time—made Facebook the go-to place for the aspiring propagandist? The most straightforward answer is digital advertising, but that only scratches the surface. Consider the following example:

- A cosmetics brand wishes to tap the—hypothetical—market of heterosexual bachelors in the geographic region of the Rhineland whose psychological disposition roughly corresponds to what we call midlife crisis.

Before Facebook, the chief propagandist of this brand would have had to physically assemble members of the target audience, then find the optimal route through a quagmire of questionnaires in order to identify the most promising marketing angles. These so-called focus groups have always had their shortcomings, owing to either insufficient sample size—i.e. the group not being representative of the whole—or the peculiarities of the group mind: the individual exhibits different behavior when surrounded by its peers, orienting its answers towards agreeability with the larger consensus so as to avoid conflict—and perhaps improve its standing within the group.

Eliphas: Facebook solved both of these shortcomings:

- There used to be the saying that “everybody and their dog is on Facebook”. Combined with the platform’s array of segmentation tools, this meant that every propagandist suddenly had a statistically significant cross section of every imaginable subgroup—and of a subgroup’s subgroups—right at his fingertips.

- As it turned out, people are more honest when volunteering intimate details of their social life to an invisible data cruncher than when questioned by a human.

In the cosmetics brand example, we thus wouldn’t be limited to impersonal mass communication. Instead, we’d be able to tailor our messages to the wariness of the middle-aged introvert and the despair of the defunct gigolo, to approach the migrant from Turkey as a fellow kinsman while embodying tradition to the Oktoberfest regular.

Klotz: Since you’re heaping so much praise on the Zuckerberg organism, you should also introduce its propaganda university. This collection of beginner-friendly online courses is designed to take neophytes all the way from unimaginative hawker to Kramer-esque levels of manipulation and treachery.

Klotz: Also, it baffles me to hear a terminology zealot such as you use the word volunteering for what clearly amounts to theft. Facebook doesn’t just harvest static profile data. It tracks and evaluates all user activity on its platform.

Eliphas: Of course, I was referring to exactly this kind of dynamic analysis. The profile data is worthless—due to still being influenced by group dynamics. It is in their interaction with the platform that users reveal their true self.

How long do they scroll through their feed? What makes them stop? What pages or profiles do they spend the most time on? At what time do they tend to log in and from where—questions easily answered by lower-level network protocols—and who do they interact with most? Who’s opinion do they value? Who values their opinion?

These are the matters of interest to a propagandist, and Facebook’s user base has indeed volunteered for examination. The platform’s business practices have been known for more than a decade now and people still keep on scrolling. As I said: the inquisitive psychoanalyst is loathed, the algorithm-infused phantom in the background is not.

Neither of us will benefit from defending the sheep, so let’s refrain from adding a moral dimension to this discussion, please.

Klotz: My apologies, Dr. Kramer. I mistakenly assumed you were to lay bare Facebook’s darkest secrets when instead I should’ve expected you to act as its mouthpiece.

Eliphas: One can’t discern Facebook’s death without understanding what grants it life. Here’s the final piece of the puzzle—access.

In the propagandist’s ideal world, he’d be an integral part of your daily routine. He’d be there when you silenced your alarm clock for the third time. When you emptied your bowels. When you raged at the BMW that cut you off on the freeway. When you logged into your OnlyFans account. When you started to develop a cough. When you bought that call option. When you pretended to care about the environment. Always observing, always nudging.

This paradise doesn’t exist—yet—but Facebook is compelled to approximate it as much as possible to remain attractive to its clientele—i.e. me.

So to summarize, Facebook’s lifeblood constitutes of three elements

- Coverage: the more people are on Facebook, the greater the value to its customer base. Onboarding the entire population would be the holy grail.

- Quality: the platform needs to provide detailed behavioral data—and analysis tools. This is the area where Facebook can exert the most control, and the machine learning models are undergoing constant refinement.

- Access:the platform’s monitoring should ideally encompass all aspects of an individual’s life. Blindspots are undesirable to the propagandist, as they might lead to false conclusions—and by extension wasted effort.

Why is this important? Because in regards to coverage and access, Facebook has been on the defensive for almost a decade now. It would already have ceased to be relevant if not for the acquisition of Instagram and WhatsApp—the acquisition of Oculus has little influence on the social media network’s day-to-day operation.

The year things started to turn for Zuckerberg was 2012.

Klotz: But this was the peak of Facebook’s pre-IPO growth.

Eliphas: Zenith would be the more appropriate word. All social networks have a finite lifetime and will eventually end up as profile graveyards.

This is due to human nature—sooner or later, people get tired of seeing the same old faces, even more so if those faces are embedded in the same old interface.

Klotz: While such a blanket statement may be true, there was nothing old about the company in 2012. It had just left Friendster and MySpace in the dust and was jacked up on the selfies of a billion users.

Eliphas: A billion aging users. Facebook had used college campuses as its staging ground. Its core user base was therefore made up of students wanting to stay up to date with the activities of their classmates as well as—I know you dislike teen drama, but this must be stated—guys seeking alternate modes of connection to that girl.

This reliance on teen hormones proved successful in the early years, as America’s college model had been exported to the entire globe. Whatever cultural and linguistic differences may exist between a drunk Harvard fresher and his counterparts at LMU Munich and Delhi University, the parameters of campus life are close enough for the Facebook formula to have worked.

However, time marches on and—with very few exceptions—these initial users wouldn’t remain students forever. They’d graduate, integrate themselves into a megacorporation, grow bald and attached to status symbols, raise a family. All the things society expects them to do.

Klotz: So in short, they’d become uncool.

Eliphas: I think you see now where I’m going with this. The college student eventually becomes a more or less functional adult. A group of adults attracts more adults. But the skater boy who has just moved into the grad’s dormitory doesn’t want to hang out with such a crowd. He wants to connect to his classmates and—yes, it bears repeating— that girl. Most importantly, he wants to do this edgy teen stuff away from the adults, not under their supervision.

Zuckerberg knew this, which is why he was willing to secure the Instagram deal with $1 billion. Keeping taps on the youth was worth any price.

Klotz: That’s not the story I’ve heard. Back in 2012, Facebook was struggling with its foothold on mobile and competition from Twitter—as well as the now forgotten ghost town that was Google+.

Instagram outperformed its own photo sharing app, so naturally the idea of an acquisition must have been floated in internal meetings. The organism’s hand was forced, however, when Twitter came up with its own acquisition offer.

Eliphas: Wrong. Facebook wasn’t battling Twitter or Google+, it was battling its own decay. Zuckerberg was on top of the world at the start of the last decade, but he was standing on a mountain of yesterday’s college culture, and the clouds were gathering on the horizon.

Why was Facebook on mobile in the first place? It was always about the youth. Those young, impressionable minds—of tremendous value to the propagandist—that just wouldn’t line up for friend requests and likes anymore.

Zuckerberg had a choice to make. He could have accepted the inevitable and worked towards a graceful exit.

Klotz: Graceful exit? There is no such thing for a social network. Friendster and MySpace may have faded from the popular mind, yet they lumber on in a state of perpetual undeath.

Eliphas: These networks simply didn’t plan ahead. If Zuckerberg had mapped out Facebook’s sunset with the care he had put into its rise—the network’s growth process had been meticulously planned—he may have discovered a more elegant termination strategy.

Who knows, an early death may even have left him in a more advantageous position than the one he presently finds himself in. He may have skirted the reputational damage of the post-2015 period while still walking away as one of Silicon Valley’s deep-pocketed paragons. In this alternate scenario, the public may even have embraced him as the Metaverse’s Lord and Savior before 2021.

Instead, Zuckerberg attempted to cheat fate. The Instagram acquisition was the first blood transfusion, the takeover of WhatsApp the second. None of them cured Facebook’s ailment. They merely staved off the cardiac arrest.

That these transfusions didn’t refill the hourglass is already apparent—WhatsApp was popular among teens at some point but is now overshadowed by SnapChat. At the same time, more privacy-conscious adults have been moving towards Telegram and Signal. So Facebook is bleeding chat data from young and old.

In similar vein, Generation Z—weighed down by the aftermath of the 2008 recession and the pressures of an algorithm-driven marketplace—eventually tired of Instagram’s wealth simulator.

Klotz: I wouldn’t pronounce Instagram dead just yet, Dr. Kramer. It is still the favorite laboratory of your peers.

Eliphas: Not for those that plan ahead. I’d much rather plant my ideas in the heads of the young than run up against the thick skull of 30-year-old Joe who’s made up his mind on the world.

To reach the young, though, I’d have to knock on the doors of our Chinese friends.

Klotz: You think TikTok is a genuine threat to the Zuckerberg organism’s well-being?

Eliphas: It is why he put up his best smile at Connect 2021. It was to assure his customer base—i.e. me—that Facebook / Meta will have a way of accessing younger age brackets.

Remember: Facebook acquired Oculus in 2014 and has spent the subsequent years in—relatively—quiet refinement of its VR tech. Carmack’s prototype simulation showcased the meager fruits of this labor. The reason Zuckerberg dropped the Metaverse bombshell this early—even though, by his own admission, development might last for another decade—is because TikTok has him spooked.

Klotz: What about Frances Haugen and the recent congressional hearings?

Eliphas: Political theater. Certainly not optimal for the engineering of consent, but a tarnished reputation is insufficient to fell a giant like Facebook—the tobacco industry has weathered worse storms and emerged with healthy balance sheets.

But TikTok is a different matter. Here is a competitor that siphons away just the kind of user data on which Facebook depends for its survival. A competitor that refuses to be bought out and is poised for rapid growth. The worst nightmare of any tech CEO.

Klotz: Am I supposed to believe that what I’m seeing in the Meta announcement video is a frightened biped?

Eliphas: If you zoom in very closely, you can see the fear in Zuckerberg’s eyes. The Meta reveal was given by a cornered animal.

Klotz: What makes you think TikTok has the staying power to defeat Facebook? New social networks spring up all the time, and they tend to implode as violently as they expand.

Eliphas: TikTok makes optimal use of the new generation’s shortened attention span and the replicative nature of pseudo-events. As Boorstin wrote in The Image:

Pseudo-events spawn other pseudo-events in geometric progression. This is partly because every kind of pseudo-event (being planned) tends to become ritualized, with a protocol and a rigidity all its own. As each type of pseudo-event acquires this rigidity, pressures arise to produce other, derivative, forms of pseudo-event which are more fluid, more tantalizing, and more interestingly ambiguous. Thus, as the press conference (itself a pseudo-event) became formalized, there grew up the institutionalized leak. As the leak becomes formalized still other devices will appear. Of course the shrewd politician or the enterprising newsman knows this and knows how to take advantage of it. Seldom for outright deception; more often simply to make more “news”, to provide more “information”, or to “improve communication.”

— The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America, chapter 4

Eliphas: The TikTok platform incentivizes its users to put their own spin on popular videos—i.e. to derive a pseudo-event from another pseudo-event—offering each of them an algorithmically fair shot at 15 seconds of Internet fame. Needles to say, the formula worked.

Klotz: You’ll have to explain this pseudo-event term to us non-propagandists, Dr. Kramer.

Eliphas: The pseudo-event is what sustains our modern world. Its properties are best conveyed by the example at the beginning of Boorstin’s book:

The owners of a hotel, in an illustration offered by Edward L. Bernays in his pioneer Crystallizing Public Opinion (1923), consult a public relations counsel. They ask how to increase their hotel’s prestige and so improve their business. In less sophisticated times, the answer might have been to hire a new chef, to improve the plumbing, to paint the rooms, or to install a crystal chandelier in the lobby. The public relations counsel’s technique is more indirect. He proposes that the management stage a celebration of the hotel’s thirtieth anniversary. A committee is formed, including a prominent banker, a leading society matron, a well‑known lawyer, an influential preacher, and an “event” is planned (say a banquet) to call attention to the distinguished service the hotel has been rendering the community. The celebration is held, photographs are taken, the occasion is widely reported, and the object is accomplished. Now this occasion is a pseudo‑event, and will illustrate all the essential features of pseudo‑events.

— The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America, chapter 1

Eliphas: As to what these essential features are, the next paragraph tries to sketch them out:

This celebration, we can see at the outset, is somewhat—but not entirely—misleading. Presumably the public relations counsel would not have been able to form his committee of prominent citizens if the hotel had not actually been rendering service to the community. On the other hand, if the hotel’s services had been all that important, instigation by public relations counsel might not have been necessary. Once the celebration has been held, the celebration itself becomes evidence that the hotel really is a distinguished institution. The occasion actually gives the hotel the prestige to which it is pretending.

— The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America, chapter 1

Eliphas: Had Boorstin written his book in the 21st century, he’d have shortened this to “fake it till you make it”. As may have become clear at this point, the entirety of social media is made up of pseudo-events, as are YouTube and the Huffington Post—and, coincidentally, the Amazon product pages for your books.

Klotz: And the Zuckerberg humanoid is about to miss out on a big batch of this pseudo-fun, I take it.

Eliphas: Not if he can pull through with his Metaverse campaign. VR and games are a combo that resonates with the youth—to some degree. By establishing himself as the owner of the virtual playground, Zuckerberg may finally be able to pull the plug on the atrophying Facebook network and start over with a clean slate.

Klotz: While remaining subject to the same time decay as before, having to rinse and repeat until the Internet collapses under the weight of Facebook spin-offs.

Eliphas: That depends on how foundational Meta’s technology will be. If Zuckerberg’s playground ends up as one of many, then rinse and repeat it is indeed. On the other hand, if Oculus VR manages to become the industry standard—the primary means of connection to the new Internet—then Meta will have earned its name.

Klotz: I guess it’s time we tried to determine the most probable outcome.

Probable Outcomes

Klotz: I’ll be blunt. Assuming the governing thought of the Zuckerberg intelligence is serious about going all in on the Metaverse, my prediction is that it’ll wind up empty-handed in an empty playground, for two reasons:

- In prioritizing VR, Facebook might be bringing a stallion to the NASCAR cup. With the company’s resources tied up in Oculus development, the BIC research area has been ceded to ambitious rivals.

- Even if John Carmack creates the perfect simulation, competing worlds such as Decentraland and Sandbox already exist. Facebook won’t be able to swallow all of these upstarts, and thus there will never be a single Metaverse.

Eliphas: Is your infatuation with the brain-computer interface concept grounded in any kind of evidence, or is this delusion speaking?

Klotz: It is grounded in this document. Our tribal oracle has computed the most probable resolution of the 21st century, with a new kind of processing unit—the Neuristor—being derived from Neuralink schematics, and a megacorp alliance seizing control.

Eliphas: Interesting, so you expect Neuralink to possess some substance after all. That obviously can’t be true.

Klotz: I agree that the prospect might sound outlandish at this point in time. You’ll have greater difficulties refuting my second argument—the Metamultiverse thesis, as I shall call it—since it’s backed by history.

Silicon Valley has never been content to disrupt the world with just one implementation of a new technology. Rather, the clash of egos has always guaranteed that there’d be multiple solutions to the same problem. Multiple PC brands, multiple operating systems, multiple email clients, multiple document formats. People could always choose between different flavors of disruption.

Take the protocol jungle that is web browsing as an example. Clicking a link initiates a flurry of activity. Low-level data packets are sent over the wire and reassembled at their destination, SSL certificate chains validated, images differentiated from video and text content, HTML and CSS files parsed according to (which?) language specification, JavaScript executed by the runtime interpreter—all while adhering to security mechanisms such as the same-origin policy. Each of those tasks represents a truckload of technical challenges. From an engineering perspective, the most pragmatic thing to do would be to sit down once and create one solution, then reuse the software on all devices. This is what we got instead:

Klotz: And these are just some of the more well-known browsers. The true number of active projects must be in the hundreds.

Of course, what starts in Silicon Valley quickly makes its way across the globe, and multi-flavored disruption has become tradition. As of January 2022, the Binance crypto exchange lists over 500 supported coins. Realistically, the world can’t have a need for 500 decentralized digital currencies. But that’s where we’re at right now anyway.

I know this is old news to you, Dr. Kramer, but our non-technical tribesmen might be surprised to hear that innovation is only an intermittent phenomenon. Most of the time, the wheels are just spinning in the mud.

Eliphas: It’s a free market, as they say. In this case, however, I’d very much prefer efficiency over freedom. All the wasted effort that goes into the development of these knockoffs. All the compatibility checks and fail-safes that have to be added to existing projects because [ insert institution here ] didn’t have the patience to write decent code. We would already have colonized Mars if it weren’t for these petty squabbles.

You were brave—though not brave enough, as you omitted the Brave browser—to list Internet Explorer instead of its successor. That Microsoft saw no other way out of maintenance hell than to eject the old code base is perhaps the finest example of the absurd heights these reimplementation frenzies can reach.

Klotz: I figured you’d be an advocate of efficiency. My allegiance belongs to the free market, as it always has. The competing solutions and conflicting standards are the woe of programmers, there’s no denying that. Unfortunately, it would seem having a subset of the adult populace regularly assume the fetal position is the price we have to pay to avoid a single CEO becoming our overlord.

The Zuckerberg humanoid may be able to overcome all technical challenges, but it won’t overcome the chaotic nature of the tech industry itself. Even as it made its Metaverse reveal, the crypto community was feverishly burning millions on virtual parcels and JPG images. With decentralization as the hallmark of all blockchain projects, the humanoid has few prospects on that turf other than being stoned as the Antichrist.

Klotz: Likewise, the other Silicon Valley behemoths certainly aren’t gazing at their navels. At the very least, we’re going to meet the offspring of the Google Glass abomination some day.

Taking all of this into account, the chances of the Zuckerbergian Metaverse becoming the Metaverse are quite slim.

Eliphas: Your logic is flawed. You presuppose elimination to be a requirement for market dominance. But Meta won’t have to destroy all other playgrounds in order to become number one.

Is there only one search engine in the world? No, there’s a bunch of them, in fact: Bing, Yahoo, Google, the maybe-privacy-friendly DuckDuckGo—and Baidu, if we count the CCP’s toys as well.

Regardless of this diversity, one engine enjoys more use than all others combined: Google—Yes, this doesn’t hold true inside China, where Baidu reigns. Since the Chinese economy is a centrally planned sham with only a veneer of capitalism, I’m sure you understand my rationale for excluding the numbers from beyond the wall.

Maneuvering his company into an equivalent position will be sufficient for Zuckerberg.

Klotz: Such maneuvering is only possible with delicate planning and swift execution. Facebook may no longer be capable of either. The company has been mired in controversy for some time now and will continue to be so for the indefinite future. Its resources are tied up in political battles. Even if all negative press were to cease tomorrow, the sullied reputation would remain.

Eliphas: You give too much weight to the negative sentiment of the moment, just as you did with Cyberpunk 2077. I will therefore repeat what I’ve said in that discussion: people are quick to forget and the Internet is even quicker.

Moral grandstanding from politicians doesn’t hurt Zuckerberg, and most of his vilest critics are probably on his payroll—politicians have to remind the plebs from time to time that they’re deserving of their vote, hence the dramatized acts of outrage.

Then there’s the crowd that slanders all things Facebook but continues using the platform. This demographic can be safely ignored.

Eliphas: You say Zuckerberg’s foray into VR is predestined to fail, even if Carmack perfected the technology. I predict the opposite. People will flock to the shiniest playground. Few will know or care about its architect. Having fun will be at the forefront of their minds.

Did concerns about TikTok’s alleged involvement with the CCP stifle the platform’s growth in the West? Of course not. The youth don’t care about such abstract things. They care about their 15 seconds.

However unpopular the name Zuckerberg may have become in recent years, it won’t keep people out of Meta’s Metaverse.

Klotz: I can’t challenge a propagandist’s verdict on public opinion. But I don’t see Facebook establishing itself as a dominant player in the race towards Internet 2.0, not by a long shot. The company faces too much resistance on too many fronts, and its war chest is not bottomless.

Eliphas: We have reached another impasse, then.

Klotz: So it seems.

Conclusion

Klotz: You borrowed heavily from Snow Crash earlier, Dr. Kramer. I hope you don’t mind me wrapping up this discussion with another passage from the book.

There’s only one Metaverse in Stephenson’s novel, but reality is more fragmented, particularly in the United States: hyperinflation has put government institutions on the retreat—eerily prescient in 2022—and the power vacuum has been filled by so-called burbclaves and Franchise-Organized Quasi-National Entities—frequently abbreviated as FOQNE in the story.

MetaCops Unlimited is the official peacekeeping force of White Columns, and also of The Mews at Windsor Heights, The Heights at Bear Run, Cinnamon Grove, and The Farms of Cloverdelle. They also enforce traffic regulations on all highways and byways operated by Fairlanes, Inc. A few different FOQNEs also use them: Caymans Plus and The Alps, for example. But franchise nations prefer to have their own security force. You can bet that Metazania and New South Africa handle their own security; that’s the only reason people become citizens, so they can get drafted. Obviously, Nova Sicilia has its own security, too. Narcolombia doesn’t need security because people are scared just to drive past the franchise at less than a hundred miles an hour (Y.T. always snags a nifty power boost in neighborhoods thick with Narcolombia consulates), and Mr. Lee’s Greater Hong Kong, the granddaddy of all FOQNEs, handles it in a typically Hong Kong way, with robots.

— Snow Crash, Chapter 6

Klotz: These are not just gated communities. They are little fiefdoms, each with its own set of laws—and methods of enforcement. Many of these entities even have their own currency. Passing from one FOQNE to another is like passing into another country.

This is what the future of the Internet will look like. Perhaps the Zuckerberg organism’s Metaverse will still be around, though I highly doubt it. But there will also be numerous other kingdoms, and gracefully moving between them without becoming the vassal of one particular lord will be the challenge of that age.

We can already imagine how these transitions will play out, technology-wise: as of January 2022, the two biggest cryptocurrencies are still Bitcoin and Ethereum. These two projects run on separate blockchains that are incompatible with each other. Yet the entire decentralized finance space, boasting fancy stuff such as automated market makers and smart loans, runs on the Ethereum network.

Initially, this threatened to exclude Bitcoin hodlers from the DeFi casino. To grant them a seat at the table, wrapped Bitcoin—WBTC—was created: a token native to the Ethereum blockchain whose sole function is to represent Bitcoin in the various DeFi games—just like the casino chip exists to represent fiat money.

We can extrapolate this into the distant future: the year is 2077 and Elon Moonshot has just entered Nintendo’s Marioverse. Looking down, he realizes that his trousers and the silver-plated Nikes have gone missing. They’ve been fabricated with Microverse protocols, which the Marioverse doesn’t support. Elon Moonshot’s rising panic quickly dissipates as a dapper sales avatar materializes at his side: MicroBridge is a service provider whose mission it is to connect the Marioverse to all other worlds. The sales avatar offers to convert the incompatible pieces of Elon’s attire—for a small fee, of course. Elon Moonshot gladly accepts. Now he’s ready to mingle.

Eliphas: With today’s tech industry as the backdrop for all speculation, such a fragmented future can be deemed probable. I don’t take Zuckerberg’s irrelevance as a given, however. Transitioning his empire from scrollable tapestry into a three-dimensional world will require biblical numbers, but he has such numbers at his disposal.

If we go by Zuckerberg’s own roadmap, then Meta still has a decade to shed Facebook’s technical and reputational baggage, eventually disassociating from the name Facebook entirely. Make no mistake: a good public relations campaign will achieve this, because—it bears repeating—people are quick to forget and the Internet is even quicker.

The best-case scenario is to build back better: finally ending all life support measures of the network-that-shall-no-longer-be-named and breaking new ground in the Internet 2.0, incidentally ushering in a new golden age for a new generation of propagandists.

Formally, Zuckerberg’s Metaverse may have to contend with parallel Metaverses—in the manner of Google formally contending with Bing and Yahoo—but his rendition may be the only one that matters, in the end.

Klotz: Charming. If only you had expressed as much faith in me.

Eliphas: Faith is not part of the equation. I deal in facts.

Klotz: You have made that clear several times, Dr. Kramer.

Eliphas: I’m relieved to hear that. I also sense that I might be overstaying my welcome, so—unless you object—I’m going to take my leave.

Klotz: I do not object. Be on your way. And may time determine which one of us is worthy of (meta) prophethood.

Eliphas: I already create prophets, I don’t have to be one.