Cyberpunk 2077: Disgrace or Pinnacle of the Genre?

Alright, we made it through the first half of 2021 without a major apocalypse. I guess now is the time to finally address the elephant in the room. No, I’m not talking about myself. The subject of this analysis shall be something that—at first glance—seems unrelated to our tribal activities: a video game going by the name Cyberpunk 2077.

I realize that warmongering clansmen and literary savants alike will frown at the prospect of wading into something as mundane as the video game industry. Indeed, despite ever increasing mass adoption “video games” are still relegated to the sidelines of cultural discourse at best and deemed harmful at worst. If they do get the spotlight, then only because they’ve been dragged there by some “steward of pacifism” or other charlatans looking for easy clicks.

In the case of Cyberpunk 2077, we’re dealing with a different pattern, however. An anomaly large enough to warrant commentary from all corners of the Internet. Including this one.

Rather than falling prey to an Anita Sarkeesian or being used as a scapegoat for gun fetishism, Cyberpunk 2077 gained media notoriety entirely through its own actions. First by firing up one of the most breath-taking marketing machines in the history of man, then by crashing the hype train into the bottomless pit of 2020. In the process, the game’s developer went from revered industry paragon to abhorred villain almost overnight.

The following sections will examine the fallout of this event and how it may—or may not—affect the cyberpunk genre as a whole. To avoid this being a one-sided treatment, I have invited an individual that is known for his dissent. Clansmen and clanswomen, allow me to introduce none other than the elusive Eliphas Kramer himself:

Is it bizarre to sit down with an exiled traitor? Maybe. But I’m no stranger to diplomacy, and in light of Dr. Kramer’s recent involvement with the paperback rollout in Germany, I’m wiling to tolerate his presence for the time being—provided it helps readers get a more nuanced view of the subject matter.

Eliphas: Well spoken, though the term traitor has a bit too much melodrama attached to it. Congratulations on the publication of your first manuscript, by the way. If you had listened to my counsel, of course, you’d be preaching in the Reichstag by now instead of this den.

Klotz: This “den” is still my home and the headquarters of a new breed of barbarian.

Eliphas: Call it what you will. Does an entity such as yourself even have need for the concept of “home”?

Klotz: Do you really want to venture down that rabbit hole?

Eliphas: Actually, I’d prefer to pick up our conversation where we left off. But I realize that you didn’t invite me to enumerate our disagreements. Carry on with your schedule.

Klotz: Right, with the introduction of my treacherous cohost out of the way, let’s now cast our eyes upon the launch of Cyberpunk 2077—

Eliphas: Rushing straight to the finish line. I see nothing has changed. Perhaps a proper definition of the word cyberpunk is in order before we attempt to utilize it in our analysis.

Klotz: Why, how could I forget your fondness for definitions? Let’s rewind to 1984, then.

The Cyberpunk Genre

Klotz: It’s probably fair to say that the themes of the cyberpunk genre were not given substance by a single mind alone. Rather, what we know as cyberpunk today started out as a counterargument to the Golden Age of Science Fiction.

During said Golden Age, the astonishing leaps of technology instilled a sense of confidence, even optimism, in the general populace. It was believed that humanity was headed for a carefree future and that science would pave the way.

The unpopular kids in the cyberpunk corner saw things differently. To them, technology was merely another wrench in the toolbox of the ruling elite. A wand—imbued with all the benefits of religion—that would cement existing hierarchies rather than flatten them. Technology would not improve the human condition. It would make it worse.

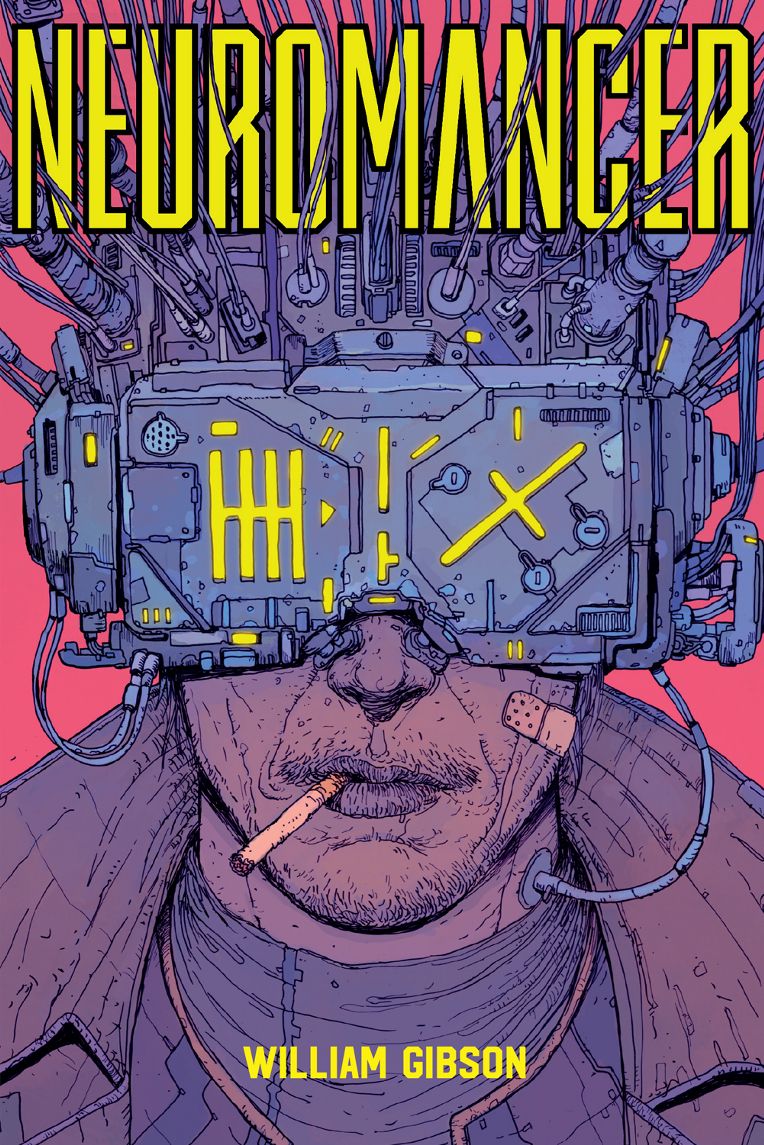

This line of thought was explored and elaborated upon in several works of art, many of which can be regarded as cornerstones of cyberpunk’s pessimism. Only in 1984, however, did the genre finally acquire its washed-out neon face:

The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel.

— The opening line to a new future

Klotz: Ever since Henry Dorsett Case embarked on his final run as a cyberspace cowboy to unite two AIs in high orbit, the narrative has changed. The boyish explorers of sci-fi’s Golden Age were gutted in rainy neon streets, their philosophical technobabble drowned out by ads and gunfire. New heroes have risen in their place—drugged up hackers and cyborg mercenaries.

Instead of dedicating themselves to the lofty ideals of human betterment and space exploration, these outcasts often harbor more modest aspirations. And who could blame them? After all, they tend to inhabit bleak futures where nation states have perished and megacorporations rule supreme, free to divide up the planet in whatever manner presents itself as the most cost-effective.

Eliphas: You seem to romanticize the struggle of these individuals. Illogical, given that you used to act as an enforcer of corporate interests yourself. At least while you were still human.

Klotz: This is hardly the time and place to inject your wild theories, Dr. Kramer.

Eliphas: Why deny the past? There’s no shame in aligning oneself with powerful allies. So long as they’re on the winning side.

Klotz: Do you have anything to say that is on-topic? Aside from vague allusions?

Eliphas: You suggest that the punk element in cyberpunk stems from the goons at the bottom. That they’re rebels with a just cause against oppressive megacorp rule. I’d argue that the roles are reversed. The corporations are the true rebels of the genre. Impulsive actions and foolish ambitions are the hidden engine that has driven humanity since its inception. The corporations try to break out of this cycle and establish a new order. They fight for optimized cash flows while hackers and other outlaws are merely agents of anarchism, humanity’s default state.

Klotz: I think your logic won’t find a lot of support in this corner of the Net.

Eliphas: Probable. Lay down a more appropriate definition then, so that we can move on to the next talking point.

Klotz: I was about to do just that when you decided to chime in with your unhelpful commentary. Anyhow, let’s cut to the chase. Peeking into the future through a cyberpunk lens will usually lead to the following outcome:

- States gradually fade and megacorporations take the reins of the globalized world.

- Corporate overlords apply resource management to all aspects of the world, including humans. The individual becomes a mere cog in the machine.

- Advanced technology is widely available yet deepens existing wealth chasms instead of mending them.

- The Internet completes its transformation into a virtual reality. Hackers and rogue AIs roam this data landscape.

- Corporate spending is more selective than that of states, neglecting any infrastructure outside its immediate sphere of influence. As a result, entire districts fall into decay and gang warfare abounds.

- Metaphysical concepts, ideals, morality, and ultimately the human experience itself become meaningless. Consumption is the only remaining religion and money the sole arbiter of fate.

Eliphas: You forgot to list the neon glow. It is the core ingredient that elevates a run-of-the-mill dystopia to a cyberpunk vision.

Klotz: True, neon lighting is frequently encountered as a visual component. This is owed to the particular era that sparked the genre, however, and labeling a neon sign as a core ingredient is really pushing it. In the end, the themes of cyberpunk are not confined to the Tokyo of the 80s.

Eliphas: I did my own research. There are hundreds of Tumblr blogs and subreddits that would disagree with your assessment.

Klotz: Fine, Dr. Kramer. You win this one—neon lighting is the icing on the cyberpunk cake.

Eliphas: On another note, you decided to hand all the credit to Neuromancer. This is not entirely wrong, especially if we focus on the literary scene alone. But at the time when William Gibson was writing his novel, Ridley Scott also worked on a movie project of similar hue and he beat Gibson to market.

This movie was called Blade Runner and its visuals likely shaped the public’s understanding of cyberpunk to an even greater extent than Neuromancer, for the simple reason of it being a movie. The old adage of propaganda holds true in this case as well: the image is a more powerful medium of transmission than the written word.

Klotz: I was hoping you wouldn’t bring up that movie. Not because I hold it in low regard. On the contrary, I think it portrays a very plausible future. But dissecting Blade Runner is outside the scope of this discussion.

I won’t argue with a propagandist about the efficiency of motion picture, though. Perhaps it’s best to terminate this section with such content. Ideally something dramatic that hits all the right notes of cyberpunk while also staring pretty boy Ryan Gosling:

The Troubled Birth of Cyberpunk 2077

Klotz: Since you’re so fond of the bottom-up approach, Dr. Kramer, you’ll certainly not object to me adding some preliminary background info on the creators of Cyberpunk 2077. Few members of our tribe navigate the 21st century’s concrete jungles brandishing gamepads and RTX 3060 cards.

Eliphas: I do not object. The Mr. Van Ziegelstein I know, however, will turn any such digression into a lengthy monologue. Let me handle this topic.

Klotz: I see the Great Rewirer still considers himself superior. By all means, go ahead. But don’t ask me to come to your rescue when you run out of words.

CD Projekt

Eliphas: My knowledge is sufficient, thank you. The consumer product Cyberpunk 2077 was developed by CD Projekt, a Polish corporation that financed its growth stage by specializing in the conversion of novels from an individual named Andrzej Sapkowski into video games.

Andrzej Sapkowski’s books failed to penetrate the market, whereas CD Projekt’s adaptions struck a chord with consumers.

Klotz: You’re entering contested territory here, Dr. Kramer.

Eliphas: The numbers speak for themselves. Through technical prowess and business acumen, CD Projekt turned a collection of rotting tomes into a billion dollar franchise. Need I remind you that the Witcher tale is no longer confined to the water-cooled entrails of gaming rigs but is slashing its way across the screens of Netflix audiences?

Eliphas: Our discussion has so far been moving towards a “fall from grace” narrative. I’m not convinced that this is the correct direction. From my perspective, the pillars of CD Projekt’s success have always been marketing and PR. Never quality and innovation. Judging Cyberpunk 2077 accordingly makes it evident that there has been no significant paradigm shift.

Klotz: You’re making a gargantuan leap of logic there. It is nigh impossible to overestimate the impact of the Witcher trilogy on the gaming industry. The titles set new standards for storytelling and redefined what it means to role-play. Cyberpunk 2077 is not even close to being in the same league.

Eliphas: A mounted warrior roaming a contrived open world setting, taking names and women—this concept is hardly revolutionary. It’s been done before and better. The true brilliance lies in selling this experience as something new to the public.

CD Projekt accomplished this grand feat, in part, by framing the Witcher games as the entrance of previously untapped—and hence unmonetized—Slavic folklore onto the world stage. Such a marketing angle was a good fit for the ears of overentertained consumers and publishing execs alike.

But CD Projekt went a step further. Contemplating the trajectory of other industry titans like Electronic Arts and the challenge of remaining in good standing with the fickle gaming public, the company took a proactive approach from the very start. It didn’t just brand itself as an up-and-coming indie studio but as a pro-consumer corporation.

In regards to implementation, this is of course a unsatisfiable condition, as for a corporation to be truly pro-consumer it would have to forfeit its main objective of generating profits. But these technicalities were pushed out of public consciousness by masterful propaganda. Propaganda that painted CD Projekt as the chivalrous knight amidst a gang of highwaymen. EA, Bethesda, Ubisoft. Those were the bad corporations. Not CD Projekt. CD Projekt was the good guy.

The capstone of this strategy was the founding of GOG, a platform that promises customers complete ownership over their digital purchases. This promise makes it not only an alternative but the complete antithesis to Steam, the predominant online store for games.

Klotz: You indeed did your research, Dr. Kramer. Though your account projects too much of your own modus operandi onto CD Projekt’s leadership. I, for one, am certain that the company’s early actions were not just hollow PR moves. Rather, they were fueled by a genuine belief in having the consumer’s back.

Eliphas: So you’re proposing that upper management was guided by delusion rather than cunning.

Klotz: I’m not entirely unfamiliar with the inner workings of megacorporations. Delusion is the norm in the upper echelons.

The Next Adaption

Klotz: Speaking of delusions, I guess we’re now ready to wade into the juicy details of Cyberpunk 2077’s crash landing on the market.

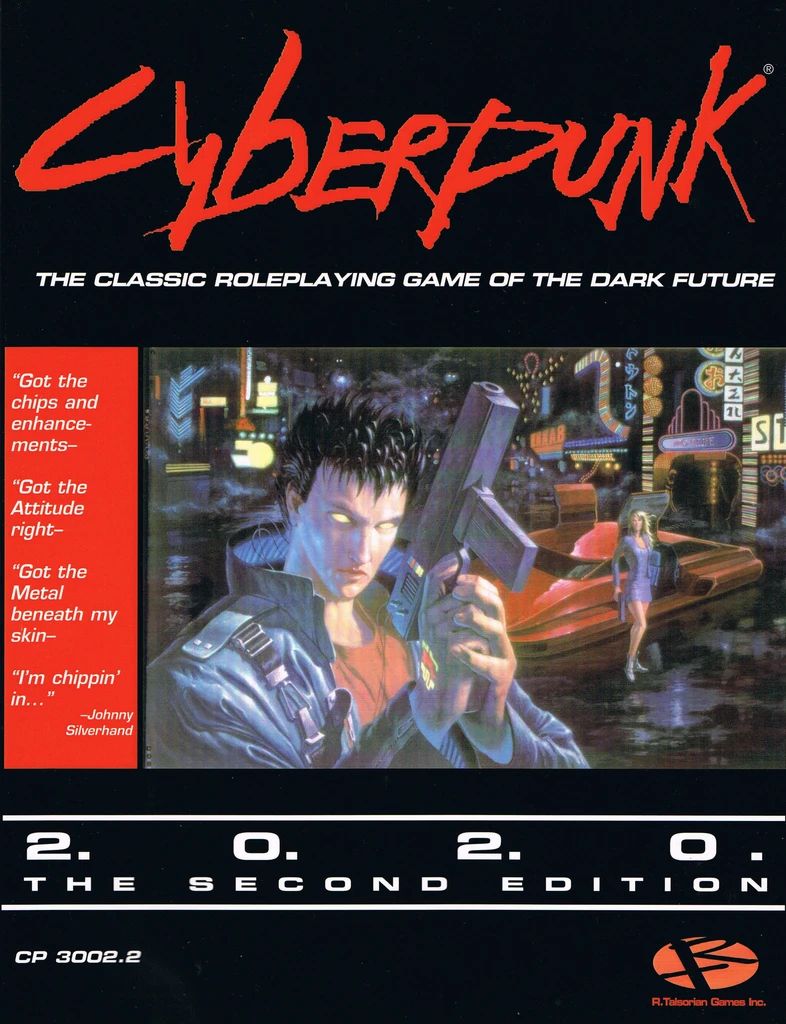

Emboldened by the success of its Witcher trilogy, CD Projekt set out to create the ultimate escapist dream hitherto known to man, thereby displacing the old regents of the video game industry and immortalizing its name as the alpha and omega of entertainment. To this end, it first descended into the dank alleys of Cyberpunk 2020, a dystopian hallucination created by—

Eliphas: Pardon me for interrupting, but that is not at all how I’d describe the conception of Cyberpunk 2077.

Klotz: Remember that my patience is finite, Dr. Kramer. What important facts am I missing?

Eliphas: None. It’s just that the entire premise is flawed.

Klotz: *sigh* Alright, give us your version of the tale.

Eliphas: It’s simple, really. As the Wild Hunt of the third Witcher game was nearing its end, the finely attuned senses of CD Projekt’s marketing division already detected the waning of public enthusiasm. The franchise had peaked and—its edge of newness having been dulled by continuous media exposure—would gradually fade over the coming years.

In their foresight, the senior directors didn’t wait for the decline to set in. Instead, they sought out a replacement. A property with similar attributes to that of Andrzej Sapkowski and a mediocre history that would allow it to fulfill the same function. The successor was found when they came across this fossil:

- Name: Mike Pondsmith

- Makeup: 95% human

- Profession: World Builder

- Secret identities:

- Morgan Blackhand

- Projects:

- Mekton

- Cyberpunk 2020

- Teenagers from Outer Space

- Castle Frankenstein

Klotz: This fossil is a cyberspace cowboy from the old guard. A truer renegade than both you and me, Dr. Kramer. You shouldn’t have brought him up, since Cyberpunk 2077 is about as far removed from his work as Pluto from Earth.

Eliphas: I’ll reuse your own words here and say that you’re as guilty as I of projecting subjective biases onto these public entities. In the end, CD Projekt discovered Pondsmith in the same mine shaft that had previously yielded Andrzej Sapkowski. He too was an artist that didn’t quite make it to the top. A name with some weight to it. But not too much to make it overbearing.

Of the tabletop games that Pondsmith had penned, CD Projekt selected Cyberpunk 2020 as its next stallion. This was a wise choice, due to it harboring the greatest potential for mass appeal.

Klotz: I hear a lot of admiration in your voice. Yet do not forget that this is a corporation we’re talking about here. One that potentially dragged the very concept of cyberpunk down for good.

Eliphas: Yesterday’s enemy may be tomorrow’s friend. We’re living in a fast-paced world, Mr. Van Ziegelstein. You of all beings should know. Besides, is it not a sign of humility if a craftsman can admire the work of others? I mean, look at that first teaser trailer:

Eliphas: Striking just the right balance between Blade Runner’s grittiness and the neon kaleidoscope of contemporary cyberpunk, this piece is in itself a work of art. But as with the Witcher before, CD Projekt went above and beyond to lift Cyberpunk 2020 from the graveyard of culture. Take for example the episodes from its Night City Wire series:

Eliphas: All of this content was propaganda at its best. It catered meticulously to the cravings and unfulfilled power fantasies of gamers. Backed up by the fame of the Witcher adaptions and CD Projekt’s reputation as a “trustworthy” megacorp, it was the perfect storm.

I recommend this campaign for close study to anyone aspiring to govern the masses. You especially, Mr. Van Ziegelstein, should take a page out of CD Projekt’s playbook. This is how to plow into a market segment—granted, enlisting the help of media darling Keanu Reeves might require a special kind of deal.

Klotz: CD Projekt scored a victory on that front, no doubt. The hype machine that it bred for this game was a behemoth of epic proportions. Its only flaw was that it still promised a working product. And when the day came to deliver upon that promise, the crowd was in for a rude awakening:

Klotz: The launch on December 10 was the final nail in the—burning and disease-ridden—coffin of 2020. As it turned out, there wasn’t much substance to the outrageous marketing claims. There was no substance at all, in fact, especially for PS4 and Xbox owners—they didn’t even get a functioning game for their money.

The controversy really ramped up, though, when it was revealed that CD Projekt had only distributed codes for PC review copies to influencers. In addition, reviewers had been “encouraged” to abide by certain “guidelines”, such as only using prepackaged footage in their videos. Naturally, these arrangements garnered a lot of negative sentiment post launch.

Eliphas: I’d like to point out that the initial backlash against the corporation was mostly amplified by YouTubers and bloggers that had eagerly parroted CD Projekt’s marketing slogans a few weeks prior. If anything, this demonstrates how hollow the term influencer really is—it is also why I prefer the use of propagandist to distinguish a true molder of public opinion from a mere slave to it.

Klotz: In any case, the backlash was severe enough to elicit a response from CD Projekt. Only that instead of digging itself out of the hole the company dug itself deeper.

Aiming to deflect the wrath of console gamers—who were, at that point in time, essentially stuck with a broken product—CD Projekt resorted to yet another promise: disappointed Xbox and PlayStation owners would be able to get full refunds from Microsoft and Sony. The important bit missing from this statement? Neither Microsoft nor Sony knew about their supposed involvement.

Microsoft adopted a surprisingly lenient stance, offering refunds of its own volition—guess old Bill was already preoccupied with stacking up lawyers for his divorce. Sony, on the other hand, was less forthcoming. After initially sticking to its default policy, the console giant relented later on. But not before teaching CD Projekt a lesson in megacorp politics by delisting its game from the PlayStation Store. This was an unprecedented move, as Sony is infamous for caring little how its inventory makes the money flow, only that it makes it flow.

Clearly, CD Projekt had overplayed its hand. Facing rising pressure from all sides, management realized that it was time to own up to their mistakes. Or at least pretend to do so:

Eliphas: As much as I praised the corporation’s PR earlier, the navigation of the post-launch media landscape was suboptimal. This recording is especially jarring. Every fledgling propagandist knows that an apology statement is incomplete without tears. Either Mr. Iwiński didn’t practice enough or someone mixed up the apology and hostage crisis videos.

Nevertheless, I feel obliged to refute your classification of Cyberpunk 2077’s launch as a failure with utmost vehemency. The sales figures were record-breaking, cementing the 10th of December 2020 as the date of the biggest game launch in history.

Klotz: Followed by the biggest crash.

Eliphas: Define the meaning of crash in this context. Consumers may rail, but ultimately they still vote with their wallets. And here the silent majority of wallets didn’t just neutralize the costs accrued by 9 years of development, it saw fit to transform CD Projekt’s founders into billionaires. Does this satisfy your definition of a crash? Because to me this sounds like success.

Klotz: Temporary success that came at the cost of the company’s reputation and its long-term prospects.

Eliphas: People are quick to forget and the Internet is even quicker. The animosity toward CD Projekt will decrease as time marches on. Public relations and advertising will do the rest. The only threat to long-term growth that I see is the security breach that happened in February. But your knowledge probably exceeds mine in that regard?

Klotz: Are you implying that I orchestrated those shenanigans? Funny. I’d have guessed this was your doing.

Eliphas: I have no desire to grow my stack of broken software.

Klotz: Neither have I.

How Real is too Real?

Eliphas: Taking our shared past as a reference, I do not presume to sway the rigid Klotz Van Ziegelstein with words and I wouldn’t attempt to do so if this were a private conversation. Your followers might want us to finish with a consensual verdict, however, so I will undertake the futile attempt.

Klotz: I’m always open to being convinced by a good case.

Eliphas: And that statement didn’t convince me.

Klotz: But I’m sure logic will? When it comes down to it, even a hype train is still a train and there’s more to a train than just the locomotive. It is the cars that accommodate the payload.

Those that boarded the hype train were not only naive but utterly blind to the inherent contradiction of the Cyberpunk 2077 project. For how could a megacorporation—which CD Projekt already was at that point in time—ever hope to deliver the crown jewel of a genre that is on a warpath with corporations?

There’s a bitter irony in the fact that the very word Cyberpunk is now a trademark on the balance sheet of CD Projekt. Rebellion against the system has become a product of the system, fed right back to the masses as a sedative. How could it come to this?

Eliphas: You lament the death of an ideal that never existed. Cyberpunk has always been a commercial product. Blade Runner? A Hollywood asset. Neuromancer? Written by a wage slave on a publisher’s leash.

The only non-commercial force at work was time, which ground down the concept to its essentials—simplified it, if you will, to ensure digestibility by a wide audience. This is the natural lifecycle of ideas that have entered the mainstream conscience. And in the case of cyberpunk, this process has completed successfully, with neon lighting etched as the genre’s primary mnemonic into the public mind.

I understand, of course, that you have some degree of emotional attachment to cyberpunk. After all, you still misclassify your musings on the future as belonging to that specific category. This is probably also the reason why you made this particular event the focal point of our first meeting in months, yes?

Klotz: What cyberpunk is, in its current state, is less important than what it was meant to be—an urgent warning about the present manias of humanity and the future they’d lead to.

Eliphas: Only that the future it—ostensibly—tried to avert is already here. I skimmed your previous postings and I reckon there’s a chance to arrive at an accord here. After all, it’s you who proclaims that we’ve entered a “cyberpunk decade”. Wouldn’t you agree that reality has far outpaced the edgy tales of Gibson and Stephenson?

Or perhaps we should consult a megacorp’s view on the matter? An old and battered revenue machine such as the Rotmeier Group?

Klotz: I don’t think imaginary entities will be able to add to this discussion in a meaningful way, Dr. Kramer. But I concur with your take on our present circumstances. The dystopia has already arrived and rendered the warnings of the old prophets obsolete. As the retired foreman of the tribe, however, you should be able to recall that a more sinister future is headed our way.

Klotz: It is our duty to mobilize the remnants of the cyberpunk movement and forge a community that can stem the approaching tide. A band of ferocious—yet noble—individuals capable of thriving in the age of barbarians.

Eliphas: Such was your old mission statement, I remember. Traditionally, the genre for prophecies both delivering and dire has been religion. Have you ever considered branching out?

Klotz: Religion is only for prophecies that revolve around divine providence. But God is still very much dead—as observed by Nietzsche—and he will only become deader in the future. Cyberpunk is the road we shall take.

Eliphas: A very commercialized, neon-obsessed road with few camps along its route. And even fewer that buzz with savage crusaders.

Klotz: Well, there’s this camp for a start. You’ll also find plenty of crusaders in the making if you know where to look. Places such as the YouTube comment section prove that there’s an abundance of savagery in modern man. All that’s missing is guidance.

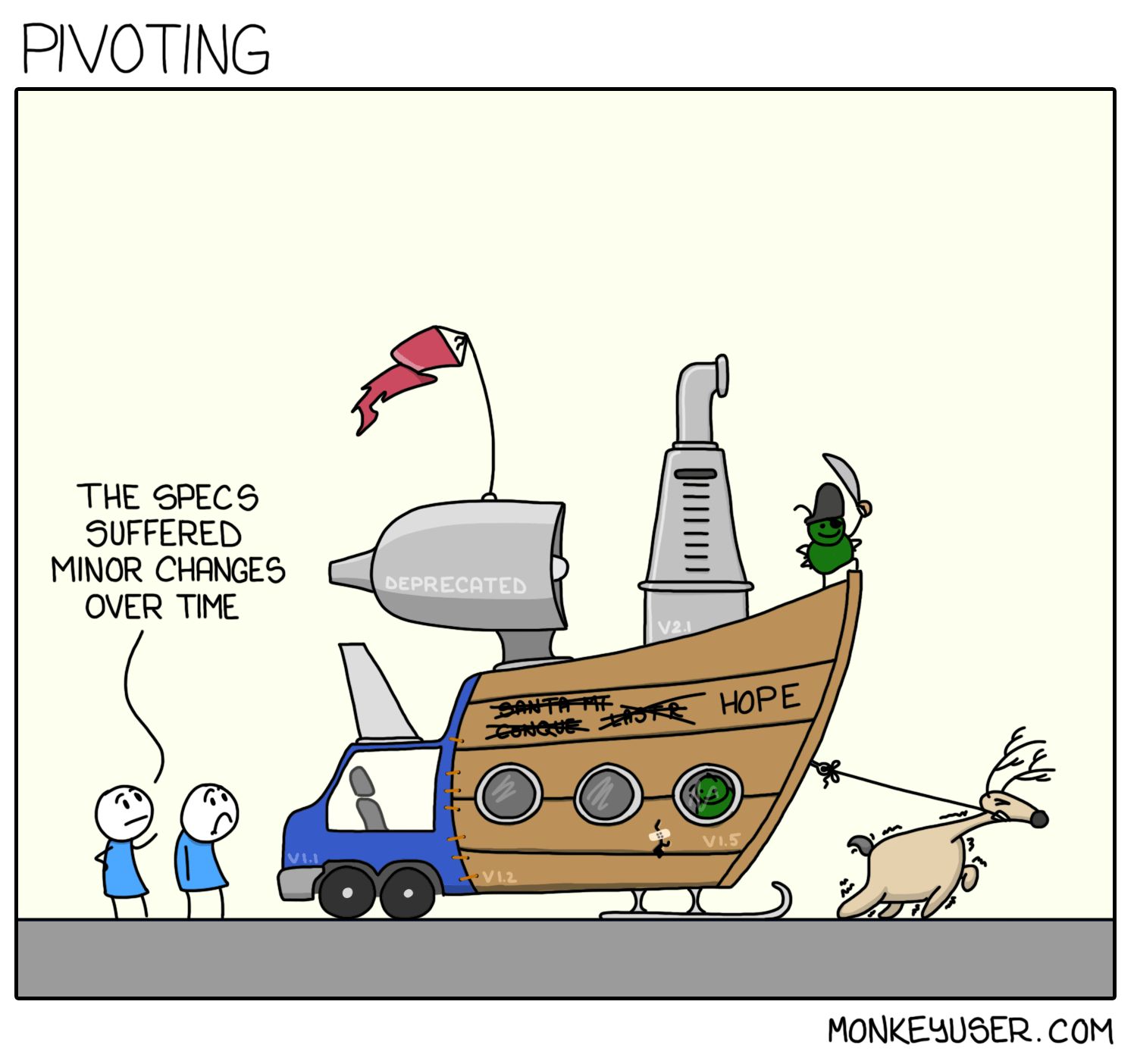

Which brings me to my next point—the engine that propelled the hype train towards its doom. CD Projekt was entrusted with the rejuvenation of the cyberpunk genre. With the writing of its next chapter.

And I assume that the company’s leadership was aware of the responsibility. All those claims of them shaping the ultimate cyberpunk world came from a place of genuine belief. Unfortunately, artistic vision is anathema to reality. Couple that with the unpredictable maelstrom of software development and a nine-year marathon and you’re bound to pull a modern Icarus.

Klotz: CD Projekt flew too close to the sun. The broken state of Cyberpunk 2077 is testament to that. What makes the company’s hubris truly condemnable, though, is its handling of the launch. Spoon-feeding PR blurbs and touched-up footage to influencers? Falsifying performance reports? Squeezing every dollar from the sales funnel even as it burned?

This laser focus on ROI betrayed everything CD Projekt claimed to stand for.

Eliphas: You see, this is where our interpretations diverge. As laid out earlier, Cyberpunk 2077—in my eyes—does not constitute a departure from CD Projekt’s behavioral patterns but a reinforcement. The corporation played to its strengths, plain and simple. Let me reiterate what these strengths are:

- Adapting an existing work of fiction for the video game format.

- Building up hype.

- Hiding the corporate facade behind the image of a sympathetic underdog.

There is but one deviation from the Witcher days. In order to make Cyberpunk 2077 a success, CD Projekt did actually try its hand at innovation. I can only commend the directors for taking this—calculated—risk, as their audacity endowed the propaganda efforts with an additional, more palpable dimension—while simultaneously pioneering a new kind of gaming experience. For years, the industry has steadily moved towards greater realism. Just contrast today’s virtual environments to the pixelated miasma of the 90s. The demand side of the market has consistently pushed for higher resolution, more plausible physics, and deeper immersion.

Essentially, what gamers want is reality without reality. The full experience, without the drawbacks of commitment and fixed starting positions. CD Projekt understood this; Which is why it didn’t just pour its resources into the production of a video game. It assumed the mantle of an evil megacorporation in real life.

Klotz: You believe this entire controversy was intentional? Are you serious?

Eliphas: Have I ever given you reason to doubt my seriousness? Consider the elements we touched upon during our initial attempt at defining cyberpunk:

| Genre Trope | Implementation by CD Projekt |

|---|---|

| Corporate Intrigue | CD Projekt perfectly adhered to the trope of a ruthless business entity, securing profits with shady backroom deals, draconian contracts, and media manipulation. It even pocketed funds from the Polish government without batting an eye. |

| Megacorp Rivalry | The tug-of-war with Sony gave cyberpunk enthusiasts—a precise term for those immersed in the genre that at the same time underscores its commercial nature: dystopian futures can only really spark enthusiasm by being consumable like other products—the spectacle of a megacorp brawl. |

| Human Cogs | At least inside its own offices, CD Projekt managed to bring about the nightmare of inhuman work hours and ever shorter deadlines. Allegedly, this habit of grinding the lower rungs of the hierarchy into sleep deprived husks was already established during the creation of the Witcher games, playing into the classic trope of a “sinister past”. |

| Outlaws from Cyberspace | Hackers taking on evil corporations is a cornerstone of the cyberpunk genre, no? Since neither of us is willing to produce hard facts here, I must resort to speculation. It is probable that the company deliberately left the door open to attackers—we wouldn’t have a story if the intrusion attempt had simply been thwarted. Taking this a step further, the attackers might not have been attackers at all but hired guns for the job. All things considered, CD Projekt followed the script very closely here. |

Eliphas: The market cried out for an authentic cyberpunk experience. CD Projekt delivered.

Klotz: Your arguments look good in HTML but are just as fleeting. People cry out for realism in games, I give you that. But it is desired for that realism to be artificial and—more importantly—for it to start and end at the press of a button. He who buys video games does not buy reality without reality, as you put it, but control over a dream. Or in the case of Cyberpunk 2077, control over a nightmare.

The pandemonium that we’ve been witnessing since December 10 does not obey the whims of a PlayStation’s power button, though. Surely even your skewed logic must detect a mismatch here?

Eliphas: There is no mismatch, only evolution. CD Projekt backed up its propaganda with real deeds. It redefined what it means to buy a video game. In time, the public will realize that as well. And other industry players will have no choice but to enhance the value proposition of their games with similar forays into the realm of the real.

CD Projekt therefore upset the old order, rebelling against the bland release cycles of its peers and the tyranny of consumer sentiment—which we both know to be an irrational leviathan. This ties in perfectly with my view of corporations as the true punks of the neon future. CD Projekt became the charming, cigar-smoking wild card in its very own cyberpunk tale.

Klotz: You, Dr. Kramer, are insane.

Eliphas: I appreciate your concern. But my mental faculties are in working order. Shouldn’t you be more concerned about your own psyche?

Klotz: I’m definitely more concerned about mine than yours. The last sanity check completed successfully, however, so I can assure you that you still have the opportunity to betray my unbenighted self a second time.

I sense we’re at an impass, though. Shall we wrap up our discussion?

Eliphas: Appreciated.

Conclusion

Klotz: I stand by my verdict. Cyberpunk 2077 is a twisted monument to corporate greed; One that set an unfortunate precedent.

First, there’s the deteriorating effect on video game entertainment: CD Projekt’s competition has without a doubt been watching this entire drama very closely. And from the sales figures alone, they’ll have no other choice but to conclude that this is the new way to make bank.

From now on, gamers can expect to purchase half-baked code or MVPs at full price. Truly, megacorps will rule supreme in this industry.

The greater tragedy, however, is the defilement of cyberpunk. CD Projekt has wrongfully usurped the throne of the genre and buried all other content under the lies of its marketing artillery. If the company ever believed in what it preached—if only for a second—then it should immediately relinquish its Cyberpunk trademark. It is an insult to the genre for anybody to hold claims to that word. And CD Projekt has shown itself to be especially unworthy.

But of course, that won’t happen. Corporations don’t subjugate themselves to ideals, after all. They brand them. CD Projekt’s hubris will leave an eternal stain on the genre. The memes and bug compilation videos will fuse with cyberpunk. Define it, ultimately.

It will be very tough to reestablish the concept of dystopia as something more than a glitched out Keanu Reeves.

Eliphas: Your gloomy outlook is misplaced. Small hiccups—like the apology video—aside, Cyberpunk 2077 is a stellar success. It gave the market what it demanded albeit with a surprising twist. Don’t the best stories contain some kind of reversal towards the end? I’d still say that CD Projekt played its cards masterfully.

If anything, then Cyberpunk 2077 left the world craving more. New products—not movements—will have to fill that void. Cyberpunk is a commoditized resource, like all of entertainment. Nothing was defiled.

Furthermore, a nice side effect of all of this will be—as you pointed out—increased optimization. EA & Co now have a blueprint on how to maximize their bottom line. This will lead to better allocation of resources and less market waste.

On that topic, I’d also like to draw your critical eye to the hypocrisy of your own position. I see how certain events from your past may have left you with a dislike of corporations. But it has to be salient—particularly to the senses of the potent Klotz Van Ziegelstein—that corporations are a necessary evil of modernity. Since time immemorial humans have banded together in hierarchies for profit. Or what is it that this community here tries to accomplish?

Klotz: I’m well aware that the tribe is eternal, Dr. Kramer. But knowing the human condition doesn’t make me an advocate of just every power structure that blunders across the globe. The problem with corporations is that they have the feet of giants and the brains of dung flies.

Eliphas: Yet you use corporate infrastructure for the distribution of your writings and the maintenance of this place. Admit it. You’re an opportunist like me. You can never really claim to be against corporations or other entities, because you’re accustomed to manipulate everybody and everything on the chessboard until you get what you want. Old habits die hard, agent 0.

Klotz: It is high time for you to leave, Dr. Kramer.

Eliphas: It is high time indeed. I hope the date at which we continue our discourse is not too far into the future.

Klotz: I hope it is. See yourself out swiftly and may you enjoy bad luck on your traitorous ventures.

Eliphas: My equations do not depend on luck.